Abadi, M., Agarwal, A., Barham, P., Brevdo, E., Chen, Z., Citro, C., Corrado, G. S., Davis, A., Dean, J., Devin, M., and others (2016), “Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.04467.

Buja, A., Cook, D., Hofmann, H., Lawrence, M., Lee, E.-K., Swayne, D. F., and Wickham, H. (2009), “Statistical inference for exploratory data analysis and model diagnostics,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, The Royal Society Publishing, 367, 4361–4383.

Chang, W., Cheng, J., Allaire, J., Sievert, C., Schloerke, B., Xie, Y., Allen, J., McPherson, J., Dipert, A., and Borges, B. (2022),

Shiny: Web application framework for r.

Cheng, J., Sievert, C., Schloerke, B., Chang, W., Xie, Y., and Allen, J. (2024),

Htmltools: Tools for HTML.

Chollet, F., and others (2015),

“Keras,” https://keras.io.

Clark, A., and others (2015), “Pillow (pil fork) documentation,” readthedocs.

Cook, R. D., and Weisberg, S. (1982), Residuals and influence in regression, New York: Chapman; Hall.

Davies, R., Locke, S., and D’Agostino McGowan, L. (2022),

datasauRus: Datasets from the datasaurus dozen.

Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., Van Der Walt, S. J., Gommers, R., Virtanen, P., Cournapeau, D., Wieser, E., Taylor, J., Berg, S., Smith, N. J., and others (2020), “Array programming with NumPy,” Nature, Nature Publishing Group UK London, 585, 357–362.

Hornik, K. (2012), “The comprehensive r archive network,” Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: Computational statistics, Wiley Online Library, 4, 394–398.

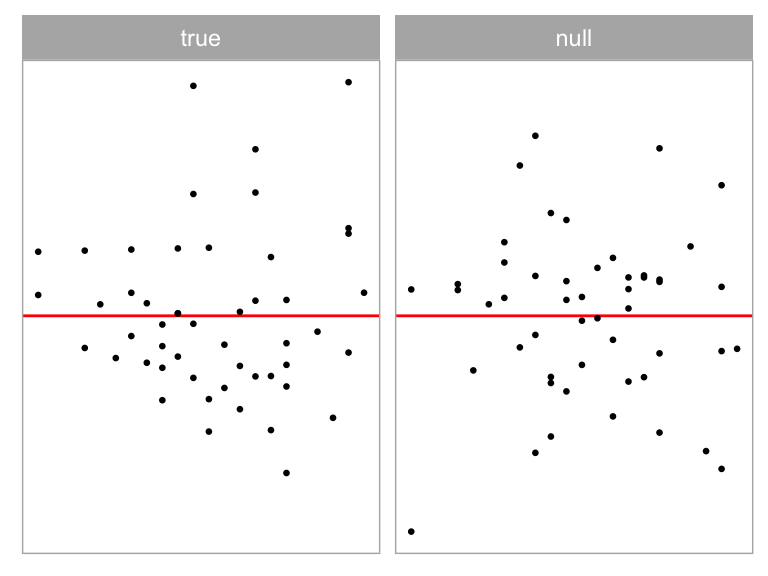

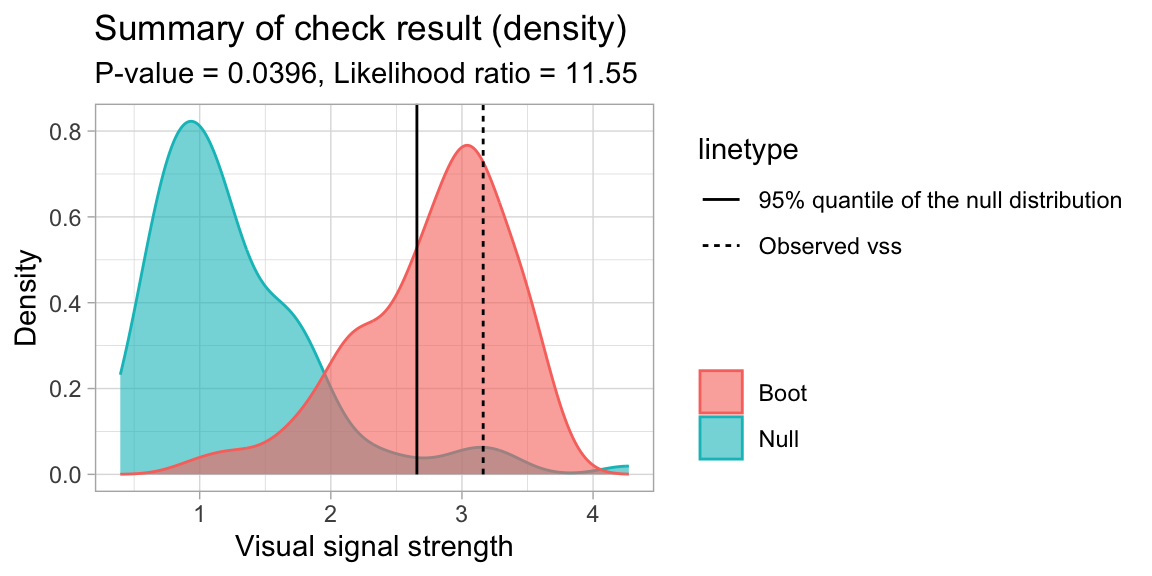

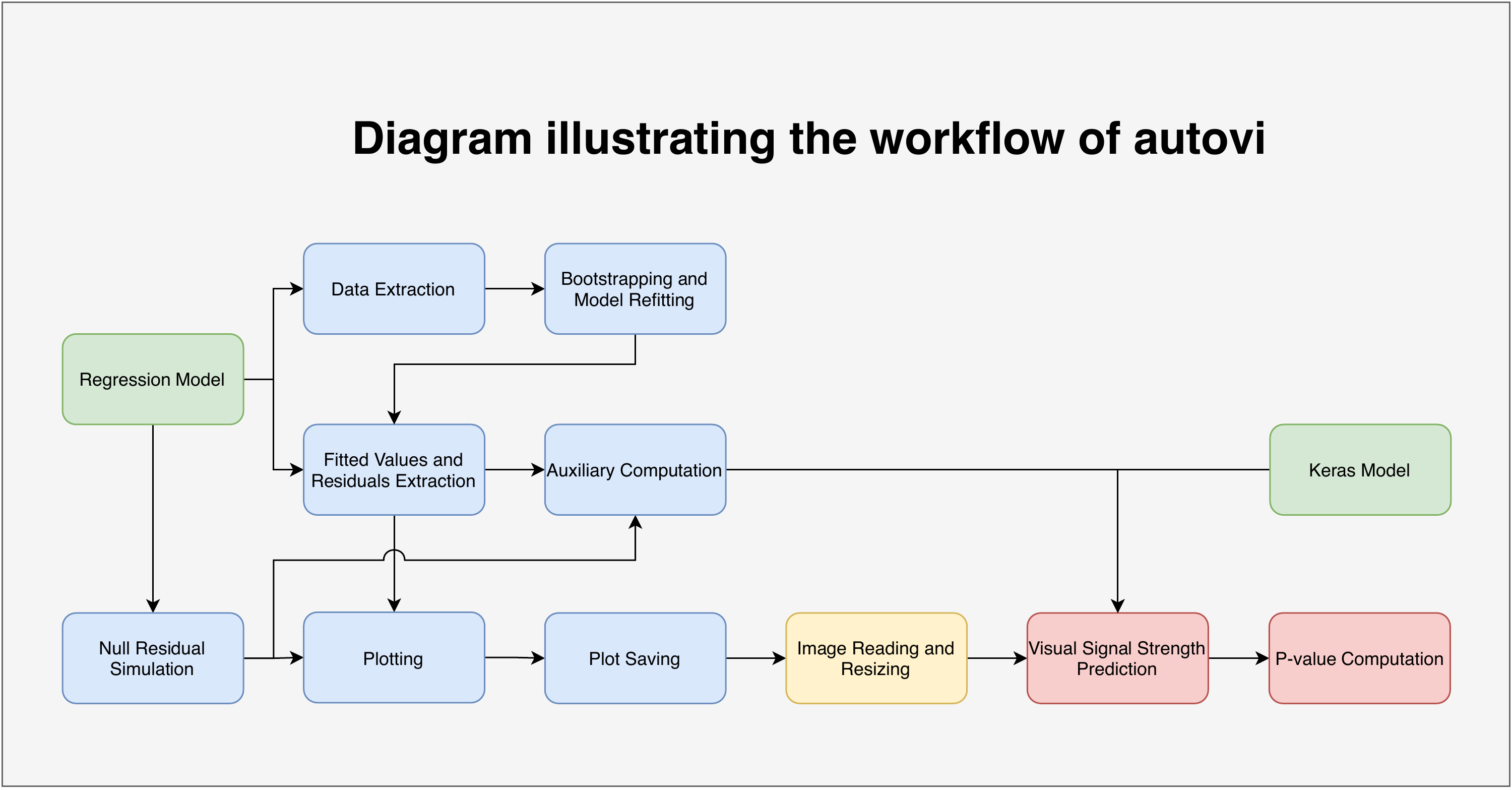

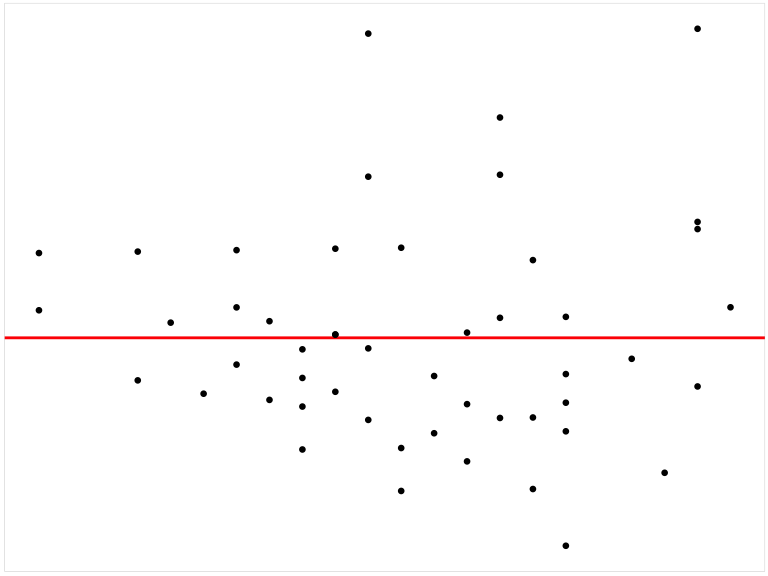

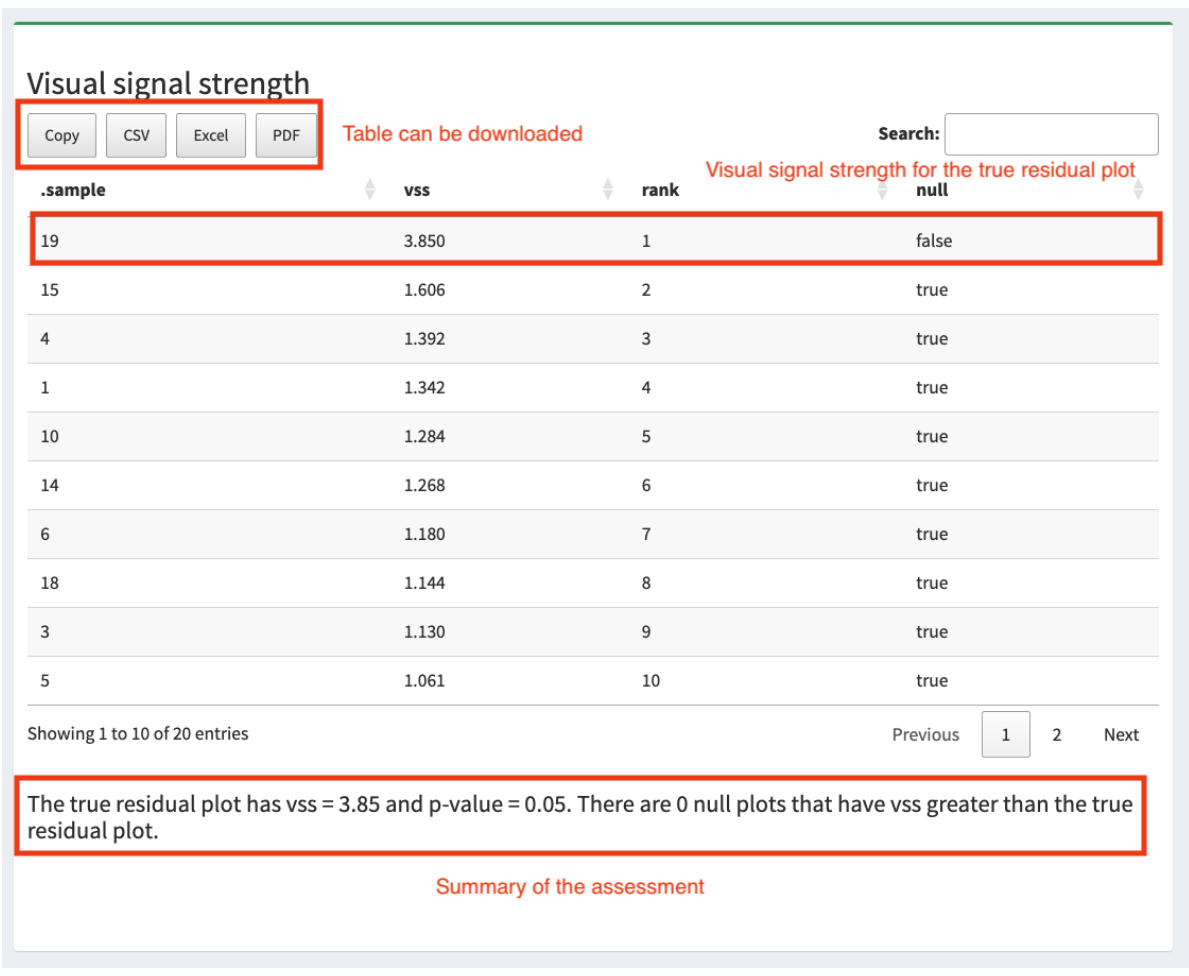

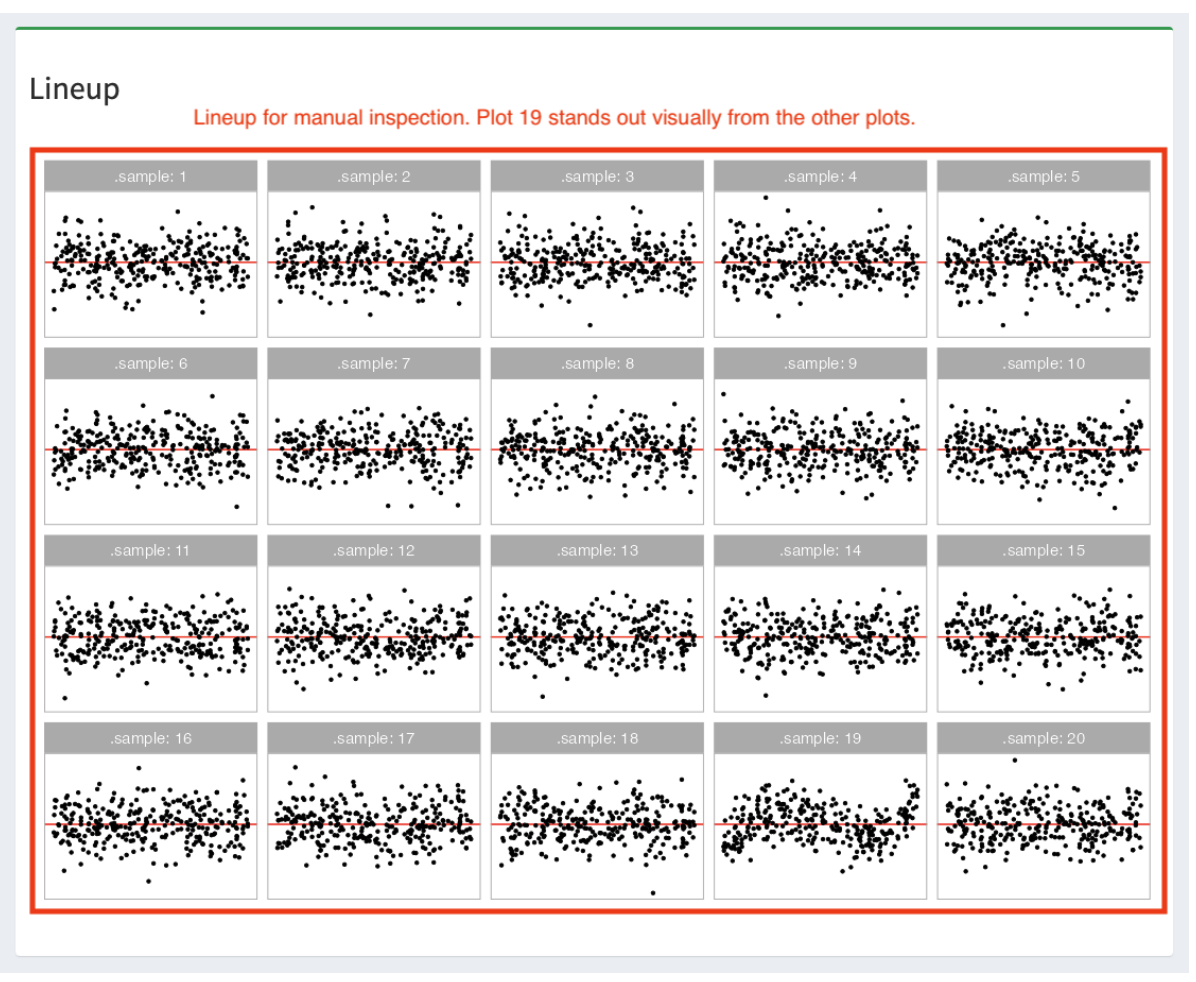

Li, W., Cook, D., Tanaka, E., and VanderPlas, S. (2024), “A plot is worth a thousand tests: Assessing residual diagnostics with the lineup protocol,” Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, Taylor & Francis, 1–19.

Loy, A., and Hofmann, H. (2014), “HLMdiag: A suite of diagnostics for hierarchical linear models in r,” Journal of Statistical Software, 56, 1–28.

R Core Team (2022),

R: A language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Simonyan, K., and Zisserman, A. (2014), “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556.

Ushey, K., Allaire, J., and Tang, Y. (2024),

Reticulate: Interface to ’python’.

Warton, D. I. (2023),

“Global simulation envelopes for diagnostic plots in regression models,” The American Statistician, 77, 425–431.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2022.2139294.

Wickham, H. (2016),

ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis, Springer-Verlag New York.

Wickham, H., Chowdhury, N. R., Cook, D., and Hofmann, H. (2020),

Nullabor: Tools for graphical inference.

Zakai, A. (2011), “Emscripten: An LLVM-to-JavaScript compiler,” in Proceedings of the ACM international conference companion on object oriented programming systems languages and applications companion, pp. 301–312.